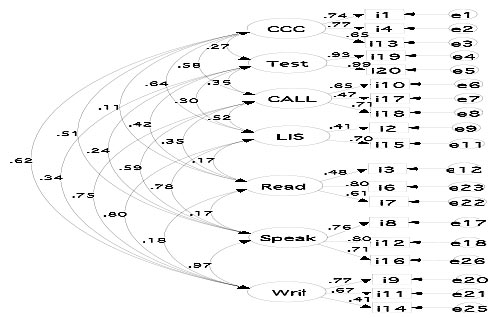

| Item # |

Items |

M |

SD |

Factor

Pattern |

| Section 1: Culture-oriented Course (α = .76) |

| 1. |

I need to learn concepts in cross-cultural communication such as cultural values. |

4.69 |

0.95 |

.74 |

| 4. |

I need to practice many activities that make me understand my own culture and aware of cultural differences. |

4.42 |

1.08 |

.77 |

| 13. |

I need to learn how to handle situations when I encounter cross-cultural differences. |

4.56 |

1.01 |

.65 |

| Section 2: CALL Course (α = .63) |

| 10. |

I need learn how to make a web page in English. |

3.07 |

1.24 |

.65 |

| 17. |

I need to take a class that uses authentic audio-visual materials such as videos, CDs, and audio. |

4.87 |

1.02 |

.47 |

| 18. |

I need to take a class that uses computers for learning. |

3.96 |

1.14 |

.71 |

| Section 3: Listening Course (α = .44) |

| 2. |

I need to practice listening to be able to understand stress pattern and intonation. |

5.08 |

0.90 |

.41 |

| 5. |

I need to practice watching dramas in English in order to be able to understand the content. |

4.69 |

1.04 |

* |

| 15. |

I need to practice listening extensively to get the main ideas. |

4.75 |

0.98 |

.70 |

| Section 4: Reading Course (α = .65) |

| 3. |

I need to learn reading skills such as reading rapidly and getting the gist. |

4.64 |

0.90 |

.48 |

| 6. |

I need to practice reading by focusing on the grammar of English texts and translating them into Japanese. |

3.79 |

1.12 |

.80 |

| 7. |

I need to study the structures of English sentences. |

3.95 |

1.00 |

.61 |

| Section 5: Speaking Course (α = .80) |

| 8. |

I need to learn to discuss issues effectively in English. |

4.33 |

1.20 |

.76 |

| 12. |

I need to practice making a speech and presenting ideas in English. |

4.42 |

1.20 |

.80 |

| 16. |

I need to take a class in which my final grading is decided based on my score on test performance such as a speech. |

4.14 |

1.07 |

.71 |

| Section 6: Test-preparation course (α = .96) |

| 19. |

I need to take a class where I solve many TOEIC, TOEFL, and STEP questions. |

4.81 |

1.16 |

.93 |

| 20. |

I need to learn test-taking strategies to solve problems in TOEIC, TOEFL, and STEP. |

4.81 |

1.19 |

.99 |

| Section 7: Writing Course (α = .64) |

| 9. |

I need to practice writing papers in English. |

4.12 |

1.17 |

.77 |

| 11. |

I need to practice writing business letters in English. |

3.71 |

1.29 |

.67 |

| 14. |

I need to take a class in which my final grading is decided based on the result of my paper. |

4.11 |

1.05 |

.41 |

PDF Version

PDF Version